Good Cop, Bad Cop: How Both Parties Keep Us Divided and Themselves Enriched

For decades, American politics has operated on a two-party system where Democrats and Republicans seem perpetually at odds. Each side accuses the other of undermining the nation, and we, the voters, are expected to rally behind one party to save the day. But what if it’s all part of a larger game, where both parties play different roles in a shared strategy to enrich themselves and maintain power through division? This “good cop, bad cop” dynamic might be the reason why, despite seemingly stark differences, neither party makes meaningful progress for the people they claim to represent.

This blog explores how this system works, why significant reforms never seem to happen, how both parties use psychology to manipulate the public, and how the rich keep getting richer. At the same time, working-class and marginalized Americans are left behind.

Democrats’ Opportunity and Inaction

When Joe Biden started his presidency in 2021, the Democrats controlled both the House and Senate. They had a rare opportunity to enact sweeping changes that could protect democracy, bolster voter rights, and put meaningful checks on presidential powers. The 50-50 Senate split meant they had Vice President Kamala Harris as a tiebreaker. They had the power but faced one significant obstacle: the filibuster.

The psychology of hope and fear played a significant role here. Democrats often appeal to the public’s hope for change, but this hope is carefully managed to avoid creating expectations that would require true systemic reform. By constantly emphasizing bipartisanship, the Democrats framed their inaction as an attempt to work across the aisle, a narrative designed to make voters believe they were the reasonable, steady party. This narrative appeals to voters who fear instability and chaos more than they desire bold action. The subtle use of fear of backlash was employed internally within the party to keep moderate members from supporting more aggressive reforms.

For months, many Democrats and progressive activists called for changes to the filibuster to push through critical legislation. The For the People Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Act could have strengthened voting rights, and the Protecting Our Democracy Act sought to curb presidential abuses of power. These bills were popular among their voter base, and they would have secured much-needed reforms.

Instead, the Democrats chose not to fight. Senators like Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema argued for preserving Senate tradition, refusing to support eliminating or reforming the filibuster. Even when it was clear that the Republicans had no intention of working with them, they held on to the idea of bipartisanship, effectively stalling their own agenda.

The irony is that the Republicans have shown, time and again, that they have no qualms about changing the rules when it benefits them. During the Trump presidency, Mitch McConnell eliminated the filibuster so that Supreme Court nominees could push through conservative justices. They are willing to use power ruthlessly, whereas Democrats, faced with the same opportunity, often hesitate and preach caution.

Historical Context: Missed Opportunities by Clinton and Obama

This pattern of hesitation isn’t unique to Biden. It goes back decades. Bill Clinton and Barack Obama entered office with significant Democratic majorities in Congress, and both had opportunities for substantial change that were ultimately squandered or compromised.

- Bill Clinton (1993-1995): When Clinton took office, Democrats controlled the House and the Senate. In the Senate, they had 57 seats, and in the House, 258 seats. Despite this advantage, Clinton’s ambitious healthcare reform—led by Hillary Clinton—failed to pass. The reform effort collapsed under pressure from moderate Democrats and powerful lobbyists, leading to the Republican Revolution of 1994, which saw the GOP take control of Congress.

- Barack Obama (2009-2011): Obama entered office with even stronger majorities—initially 58 Senate seats, which later grew to 60 with support from independents and a significant majority in the House. Obama’s administration did pass the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Still, it was a heavily compromised version without a public option, largely due to pressure from centrist Democrats and the healthcare industry. Other potential reforms were watered down or abandoned, like aggressive climate action or Wall Street accountability.

The psychology at play here was about creating the illusion of progress. Both Clinton and Obama campaigned on bold promises, and when they entered office with majorities, they created hope that transformative change was imminent. But by compromising or abandoning their boldest plans, they aimed to temper expectations and keep powerful interests on their side. This careful balancing act relied on maintaining enough progress to appease their base while avoiding changes that would disrupt the status quo. This tactic leverages cognitive dissonance—voters who want to believe in their chosen party will rationalize the inaction as strategic or necessary rather than betraying campaign promises.

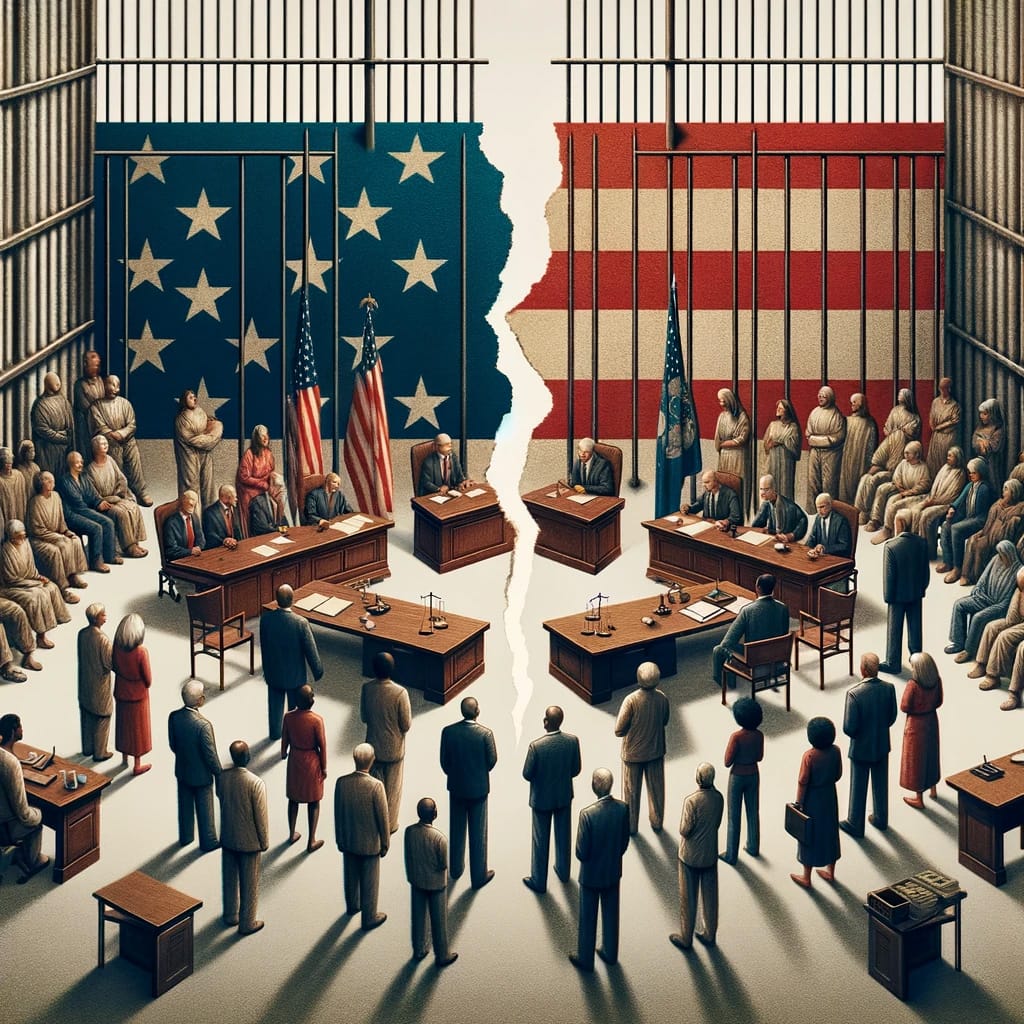

The Good Cop, Bad Cop Dynamic

Here’s where the good cop, bad cop analogy comes in. The two parties play their parts to perfection. Democrats are the “good cops,” promising reform, compassion, and progress. They appeal to voters who value equality, human rights, and the environment. Republicans play the “bad cop,” appealing to voters who value strength, tradition, and small government, often pushing aggressive policies that spark backlash. This dynamic helps divide the American public neatly into two camps based on personality and values.

The psychological tactic here is fear-based polarization. By keeping voters in a constant state of anxiety about what the other side might do, both parties ensure loyalty from their respective bases. Democrats emphasize the threat Republicans pose to democracy and civil rights, while Republicans stoke fears about socialist policies and cultural change. This perpetual fear keeps voters from considering alternatives and reinforces the two-party system. Group identity also plays a key role—voters align with the party that represents their perceived values, and any criticism of their party is seen as an attack on their personal identity.

The result is that each party keeps its base scared of the other side. Democrats warn of the destruction that Republicans will bring, and Republicans paint Democrats as radical socialists. But ultimately, the common goal of both parties is self-enrichment and maintaining power. They work to protect their own interests and those of their billionaire donors, rather than enacting the sweeping reforms that voters demand.

This explains why, even when one party has the power to make significant changes, they often fall short. The Democrats had the power to push major reforms during Biden’s first two years, but they chose to hold back, making only incremental changes while focusing on avoiding political risk. When Republicans regain power, they often reverse whatever minimal progress was made, pushing the country two steps back. This cycle ensures that no real progress is ever achieved.

Reverse Progress: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The pattern is predictable. Democrats gain power and take a small step forward. They pass some minor legislation, make some surface-level progress, but leave the bigger changes unaddressed. Then, the pendulum swings back, and Republicans take control. They undo whatever progress was made and then some. They use the power to enact policies that serve corporate interests and the wealthy while pushing cultural and social policies that divide the country even further.

The psychology here is about managing expectations and manipulating hope. By providing just enough progress to keep their base hopeful, Democrats maintain voter loyalty without risking the backlash that might come from bolder action. Republicans, meanwhile, play into fear and resentment, positioning themselves as protectors of tradition against the creeping changes pushed by Democrats. Both sides effectively keep their voters emotionally invested without delivering lasting change.

This cycle is frustratingly effective. It keeps voters perpetually hopeful that the next election will bring change, and keeps us angry at the opposing party. Meanwhile, it keeps the wealthy donor class happy and ensures that the status quo is never truly threatened.

Self-Enrichment at the Expense of the People

Another telling aspect of this dynamic is the wealth accumulation that takes place while in office. Many politicians enter government with modest means and leave with immense wealth. This comes from several sources:

- Lobbying Jobs After Politics: After leaving office, many politicians move into high-paying lobbying jobs, leveraging their connections to influence policy on behalf of corporate clients.

- Stock Trading: Despite public outrage, members of Congress are still allowed to trade stocks, and they often do so with access to information not available to the public.

- PACs and Donations: Campaign donations, Super PACs, and other forms of funding often find their way into the personal networks of politicians, enriching them beyond their government salaries.

The psychological strategy here is about normalizing corruption. By framing wealth accumulation as a natural part of a successful political career, politicians minimize public outrage. The narrative of “everyone does it” plays into learned helplessness—voters feel that corruption is inevitable, and therefore, see no point in demanding accountability. This demoralization ensures that politicians can continue to enrich themselves without significant pushback.

All of this points to the real goal of both parties: self-enrichment and power preservation. They serve the interests of the wealthy elite who fund their campaigns, not the working-class Americans who vote them into office. The decisions they make reflect this reality, focusing on maintaining the status quo rather than challenging it.

The Solution? Structural Change

If we want to break free from this cycle, we need structural reforms that challenge the grip of the two-party system and reduce the influence of money in politics:

- Campaign Finance Reform: Limit the influence of billionaires and corporations in our elections by imposing strict regulations on donations and implementing public campaign financing.

- Ranked-Choice Voting: Introduce ranked-choice voting to break the stranglehold of the two-party system and make room for more political perspectives.

- Term Limits and Lobbying Restrictions: Impose term limits on members of Congress and restrict former lawmakers from lobbying after they leave office. This would help curb the revolving door between government and corporate interests.

Conclusion: The Bottom Line

The “good cop, bad cop” dynamic has kept American voters divided and distracted for far too long. Both parties are more interested in maintaining power and enriching themselves than in making meaningful progress for the people they represent. The cycle of one step forward and two steps back only serves those already at the top, while working-class Americans continue to struggle.

To change this, we need to rethink the system. We need to demand more from our leaders, challenge the influence of money in politics, and support reforms that will give power back to the people. Only then can we break the cycle and begin to make real progress.

Support The Virtus Press

The Virtus Press is committed to bold, honest commentary that challenges the left and right alike. If it needs to be said, we say it.

If you enjoy our content, please consider donating to help us continue doing what we do best.

Your contributions allow us to sustain and enhance our mission.

Follow me on Bluesky for updates on this and other topics that shape our nation’s identity.